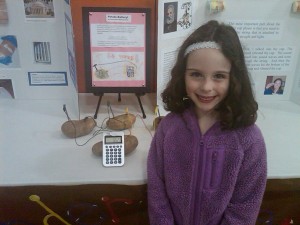

Potato batteries

Laurel went through a rite of passage last week, her first science fair. This was a non-competitive event, an Arts and Technology Night organized by her school. She really wanted to exhibit something so we got her signed up.

After looking online for ideas, Laurel chose to do food batteries. Batteries are very simple — two electrodes and an electrolyte will make one. Lemons, tomatoes, potatoes, and a variety of other foods will work. We opted for potatoes as a stable material and minimally corrosive with respect to the electrodes (meaning that they last for a long time). We used galvanized nails — nails covered with zinc — for one electrode; and pennies for the other. Alligator clips were used to connect multiple potatoes in series.

I thought this would be a pretty trivial project, but as usual, there were some wrinkles. The coating on the nails was thick enough to impede conductivity with the alligator clips. Version one, I filed off part of the coating; version two, I broke out the Dremel and used the wire brush to get the coating off, a much prettier result. We initially tried copper wire from the craft store for the copper electrode, but that had some varnish on it that caused problems. The pennies worked well as a substitute.

Each potato yields approximately 0.7V. I was impressed with this; a typical small battery gives 1.5V. But potatoes are extremely current limited. At best, they yield 0.2-0.4mA. I ordered some low-current LEDs, and did get them to light up. They are extremely small and dim so I didn’t think this would be an effective display. A little hunting on YouTube showed various potato battery videos. A few people were using calculators as the powered item. It turns out, those liquid crystal displays use very little current — and as I thought about it, I hadn’t changed my calculator batteries in years. I opened it up, removed the batteries, attached the alligator clips to the terminals, and voilà. A working calculator with an empty battery chamber.

I was very happy to have this working. The next day we looked at it again and it didn’t work. There was voltage but no current. I believe this is because the punctured skin of the potato caused it to dry out in that area. By moving the electrodes to new spots, the potato “revived” and became useful again. This meant that we would have to assemble the project on-site the evening of the show.

The alligator clips tended to fall off the calculator. Not too surprising, as the calculator was not designed to be powered this way. I made the mistake of trying to solder on a wire to the negative terminal, and was a little bit careless as to method, ultimately ruining the calculator. A sad moment, as this calculator had been with me for 15 years. A quick trip to the drugstore got us another one for $5. For the experiment, this new one was an improvement: a larger display, and very low current / power requirements. It can run off either a coin battery or solar power, with power consumption in the microwatt range. I think if you breathe on it, it will run. At any rate the potatoes certainly had no trouble with it. I taped over the solar cell and once again we were in business.

Some adventures getting the project to the school and set up, which I will skip over. Lesson there, as always, personal involvement is important. I was there early, definitely a good thing. After we were ready, I wandered around and saw a boy whose project involved the exact same solar robot that Holly and I had recently made. Like us, he had difficulty with the power connections, and was looking rather despondent. Having been through this I was in a perfect position to help, and I got it hooked up for him. His mother was very grateful!

Laurel was one of four kindergarten displays, and she was the only one from her class. Supposedly the science exhibition was to start at 8pm, but since this was the most interesting part of the evening (in my humble opinion) people were wandering in from 6:30 on. Kids loved playing with the calculator, so we had to keep an eye on it, as the clips would periodically come off. The principal stopped by and had a nice conversation with Laurel about her project.

Our idea was not completely original. There were two other food battery projects. One was another potato battery one, but done from a kit, so they had nice zinc and copper strips, as well as a few small electronic devices to show it off. The other was a bit more original (though still starting from a kit I think) and used a variety of batteries, including potatoes, lemons, soil, and the human body. There were some excellent experiments at the show. One family had four kids with displays, one of them the potato battery kit. The father stopped by and was very complimentary, saying (correctly) that it is harder to do something homegrown than a packaged project.

But, packaged projects have some advantages, and we discovered this. Our power connection failed after excessive use, pulling one of the terminals out of the calculator and rendering it inoperable. Laurel was extremely upset. We had redundant supplies for everything except the calculator — the drugstore only had one — so that was the end of the demonstrations. Still, we had a great time and learned a lot. I’m sure there will be more science fairs in our future!